|

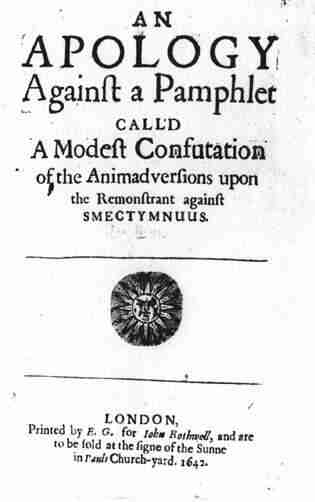

An Apology

Against a Pamphlet

| This is a response to a pamphlet

(supposedly authored by Bishop Hall and his son) entitled A Modest Confutation of the

Animadversions. Essentially, Milton has been called out for the vicious invective of

his previous pamphlet, the Animadversions. An Apology is one of the lesser

pamphlets, but it does contain some valuable early autobiographical material. Major points

- Milton "resolved . . . to stand on that side where [he] saw

both the plain authority of scripture leading and the reason of justice and equity

persuading . . . " in the debate over Church organization.

- "Rear and dull disposition, lukewarmness and sloth" are

equated with the "affected name of moderation"; "true and lively zeal"

is disparaged as "indiscretion, bitterness and choler . . ."

- Comparison of the "fame of his elder adversary" with the

"calculating" of Milton’s "years" (youth).

- Milton’s project is "to give a more true account of

[himself]" than was given in the Halls’ pamphlet.

- His best defense would have been silence, but Milton claims he is

defending the truth when defending himself: "I discerned his intent was . . . through

me to tender odious the truth which I had written."

|

|

Justification (autobiography)

section:

- University "fellows" wanted Milton to stay.

- Milton’s response to the "vomited out thence"

description of his university experience: the body keeps the worse while vomiting the

better—a weak argument at best.

- Mornings spent reading.

- Response to whoring charges (made sarcastically by the Halls): how

can a reader know that Hall is not speaking of himself and his own experience? (A

"takes one to know one" kind of argument.)

- The Confuter must know that "old cloaks, false beards,

night-walkers and salt lotion" are elements of a bordello from personal experience,

in order to be able to charge Milton of impropriety for such mentions in his Animadversions.

- Snide reference to sexual content in passages from Hall’s

earlier satire Mundus Alter et Idem—indicative of Hall’s being a bordello

regular?

- Reading as moral preparation.

- Separation of art from the morality of the artist.

- He who would be a true poet (like Milton) must be of high moral

fiber.

Reading history:

- "lofty fables and romances"—Arthurian/Ariosto

- Plato and Xenophon

- Bible/Christian religion

- Milton argues that he never could have been guilty of the things

he is accused of in A Modest Confutation, because of this moral education through

reading.

Arguments against A Modest Confutation:

General Remarks

- "This tormentor of semicolons is as good at dismembering

and slitting sentences, as his grave Fathers the Prelates have been at stigmatizing and

slitting noses."

- "Our inrag’d Confuter . . . like a recreant Jew calls

for stones"—response to call for stoning of Milton in A Modest Confutation.

- "To be the Remonstrant is no better than to be a

Jesuit."

Point by Point Refutations

Section 1

- Violence done to a holy prelat? Milton writes that he did not

know it was a holy prelate, for "evil is written of those who would be

prelates."

- "Prelaticall Pharisees" –Contrast this to Bishop

Hall’s Pharisaisme and Christianity (1625).

- Defense of harsh language: Christ used it; Luther used it.

"There may be a sanctified bitterness agaist the enemies of truth."

- "If therefore the Remonstrant complain of libels, it is

because he feels them to be right aimed." Milton accuses Hall of never having

objected to ad hominem techniques before he found them aimed at him: "How long

is it simce he hath dis-relished libels?"

Section 4

- "In what degree of enmity to Christ shall we place that

man then, who is so with him, as that it makes more against him, and so gathers with him,

that it scatters more from him?"

- Milton runs over his arguments again—Scripture vs. Tradition,

and anti-ceremony/anti-liturgy arguments.

Section 5

Milton takes Hall to task for ducking his responsibility for, and

complicity with, the ex officio oaths: "that the Remonstrant cannot wash his

hands of all the cruelties exercised by the Prelates is past doubting."

Section 6

- Milton takes Hall on for criticizing his "simile of a

Sleekstone," which, according to Hall, "shewes [Milton] can be as bold with a

Prelat as familiar with a Laundresse."

- Milton argues that the "lacivious promptnesse of his

[Hall’s] own fancy" shown in Hall’s early satires causes Hall to reach such

a conclusion. This is a "He must have a dirty mind" kind of argument.

Section 10

- Milton takes on the contention (in AMC) that "a rich

Widow, or a lecture, or both, would content me [Milton]."

- "I think with them who both in prudence and elegance of

spirit would choose a virgin of mean fortunes honestly bred, before the wealthies

widow."

Section 11

- Milton argues against Hall’s argument for

"expedience of set forms" in church services.

- He also argues against Hall’s assertion that Liturgy "is

the preserving of order, unity, and piety."

Section 12

Milton argues against Hall’s defense of rewards for the

clergy.

|

The Atheist Milton

Michael Bryson

(Ashgate Press, 2012) |

|

Basing his contention on

two different lines of argument, Michael Bryson posits that John

Milton–possibly the most famous 'Christian' poet in English literary

history–was, in fact, an atheist.

First, based on his association with Arian ideas (denial of the

doctrine of the Trinity), his argument for the de Deo theory of

creation (which puts him in line with the materialism of Spinoza and

Hobbes), and his Mortalist argument that the human soul dies with

the human body, Bryson argues that Milton was an atheist by the

commonly used definitions of the period. And second, as the poet who

takes a reader from the presence of an imperious, monarchical God in

Paradise Lost, to the internal-almost Gnostic-conception of God in

Paradise Regained, to the absence of any God whatsoever in Samson

Agonistes, Milton moves from a theist (with God) to something much

more recognizable as a modern atheist position (without God) in his

poetry.

Among the author's goals in The Atheist Milton is to account

for tensions over the idea of God which, in Bryson's view, go all

the way back to Milton's earliest poetry. In this study, he argues

such tensions are central to Milton's poetry–and to any attempt to

understand that poetry on its own terms.

|

|

The Tyranny of Heaven

Milton's Rejection of God as King

Michael Bryson

(U. Delaware Press, 2004)

|

|

The Tyranny of Heaven argues for a new way of reading the figure of

Milton's God, contending that Milton rejects kings on earth and in heaven.

Though Milton portrays God as a king in Paradise Lost, he does this

neither to endorse kingship nor to recommend a monarchical model of deity.

Instead, he recommends the Son, who in Paradise Regained rejects

external rule as the model of politics and theology for Milton's "fit

audience though few." The portrait of God in Paradise Lost serves as

a scathing critique of the English people and its slow but steady

backsliding into the political habits of a nation long used to living under

the yoke of kingship, a nation that maintained throughout its brief period

of liberty the image of God as a heavenly king, and finally welcomed with

open arms the return of a human king.

Review of Tyranny of

Heaven |

|